By Carl Valle

Just by typing a few keywords on the Google search bar, a coach will get a rather exhausting list of suggested resources. Coaches and athletes can choose from an array of how-to guides, videos, books, and online resources such as blogs. I have read everything but have found the best way to get the most effective information is a simple visit, be it a local coach or someone requiring a trans-oceanic flight. I never performed Olympic lifts until after college, and it was the first gap I had to fill with education. Coaching track and field forces one to know a little about everything, since most of the sport is performance. Since the late 1990s, I have watched hundreds of athletes being coached by some amazing coaches and found a handful of tips that are my staple techniques for weightlifting. Along with each tip or suggestion, I give the common problem, the solution application, and the origin of where I got the information. It’s important not only from an ethical perspective—we give credit to where we get information—but a historical reference also allows the reader to see the interpretation of the original source. You, the reader, may draw different conclusions, but at least a line of thinking is shared when one is told how the information was exchanged.

Take Video and Measure Bar Velocity

Video cameras and power measuring devices have been around for years and are nothing new, so why are they listed? Simple. Most abuse the simplicity and availability of video and power measuring devices by not using them correctly. The use of smartphones has helped many coaches and athletes, but a growing problem is that getting video and maximizing video are hardly the same. A similar problem exists with linear positional transducers and other tools getting bar speed that video experiences. Getting kinetic (forces) and kinematic (motion) data is the starting point, and if you are not capturing the data correctly, it’s extremely limited. Coaches and athletes care about performance output or the ability to use specific power qualities to help with improving success directly or indirectly. Using both data sets, kinetic and kinematic information, coaches and athletes can see why things are working or not working, not just raw scores. Video being so readily available from smartphones has failed to capitalize on analysis since anyone, regardless of education can capture a clip and show it in slow motion. The consumer now has video literally at their fingertips, but the needle has not moved much for several reasons. First, capturing video correctly requires a coach to have video at the correct angles, from the side or from the front, head on. Other positions, such as a three-quarter view, are great for those looking for instant feedback, but finite measurements of video are impossible to do accurately unless you are measuring from right angles. To break down both the kinetic and kinematic into a simple checklist, I distilled the best practices of both video and bar speed into three key tips that I found to work for me.

Video Capture and Analysis Guidelines

The priority of getting good video, editing clips, and doing analysis is an even distribution of effort and time. Video is underrated while it’s highly utilized, but often neglected because no real best practice exists with sports training. Here are three simple tips to doing video better with training and sometimes competition.

Mount a Camera — Obviously, getting film is the first step, and the best tool with which to do so is a mounted camera. Using a smartphone is okay, but passive acquisition of video allows for simultaneous coaching and videography. Mounting the camera is tricky, since most lifts from the side or front also struggle with random athletes walking in front of the camera. A good solution is to put the camera near a rack farthest to the side where less traffic is. Some cameras use remotes making it easier for post training editing with trimming in advance, rather than cutting clips up later.

Edit and Analyze — Coaches can approach video by an intensive review, a quick check on one variable, or something in-between. Just doing a simple analysis, coaches can create a checklist of the areas they feel are necessary to have excellent technique. Using Dartfish and other video analysis tools is a great way to show what needs to be addressed and what needs to be left alone. Even if raw clips are trimmed and sorted, one can go back later when time is available and analyze further. To keep things sustainable, do roughly half of what is on a wish list.

Share and Organize Videos — Instant feedback is very useful, but in group settings, it’s difficult because a coach must be instructing during the rest periods of individuals. Some facilities set a 5-second delay on their flat screens to allow the individual to take ownership of their technique and performance. If this is not available or philosophically a team wants to remove the “screen time” while training to another part of the day, pushing out videos is more than just uploading to a YouTube channel. Videos should be organized just like any other file or data. Athletes should be students of their training, not just students of their sport.

Bar Velocity Guidelines

Tendo Units and Gymaware have been used by teams for years, but most are just scratching the surface of what can be done. Some new wearable technologies are trying to get a slice of the pie, and most just do enough to try to convince investors but fail to make real coaches happy. I have used and tested every product available, usually before they are even public, and it’s not about the features but about the purpose of the device. At the end of the day, it’s how you use training tools, not the cool features, that drives success.

Stop Cheerleading and Start Leading — Some of the most explosive Olympic lifters have the quietest and most humble coaches, but many performance coaches scream too much. With the latest rock and rap music blaring at highly motivated individuals, do we really need more screaming? Leadership is when a coach can keep a group focused, cooperative, respectful of the process, and positive. By switching to a subtle approach and letting the numbers speak for themselves, it saves the ace of spades vocally for times when you need it.

Focus on technique for better output — The lifts are natural generators of effort, so it is wise to invest time in learning how forces are created mechanically and then just ask for more wattage or bar speed. Having an objective, visible measurement and making the athlete aware of it will increase arousal and create more output. The transparency of the effort with instruction is perfect for working with groups.

Manage power, do not monitor fatigue — What creates fatigue creates adaptation, provided enough rest is present in the program. The effect of monitoring fatigue is similar to the outcome of taking nocebos or receiving injuries. Coaches know that athletes have to focus on objective changes and be positive, but a simple cultural change and word selection can also make a big difference. When generating more power is a priority over not getting tired, behavior and lifestyle changes are more likely to occur. Athletes have dreams, so their attention and efforts should be focused away from negative consequences and on tangible goals.

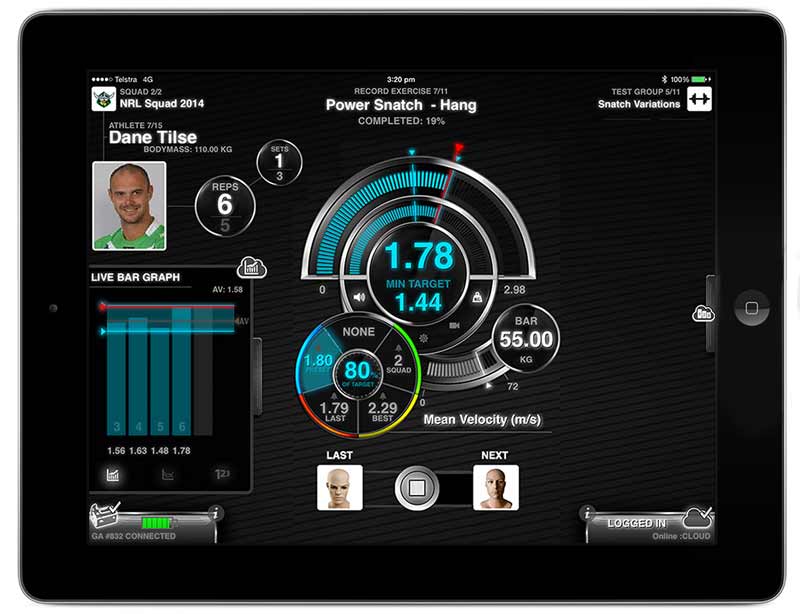

Figure 1. The Kinetic Performance platform fulfills force and motion capture, analysis, and display needs. Coaches can get athletes to see instant feedback and can have the data displayed on a leaderboard to motivate and guide them.

Lift Off Correctly from the Beginning

Perhaps the strangest trend in sports training is the use of conventional deadlifting over doing lift-off work for the Olympic lifts. I personally believe that the reason coaches are not doing more lift-off work with a clean and snatch is because their demands in knowing more exercises is diluting their mastery of the core exercises and their variations. I have looked at motion capture, pressure mapping, and sEMG with the two exercises respectively, and frankly, I have removed conventional deadlifts from my program. While lift-offs don’t usually have the eccentric benefit like most exercises, the benefits outweigh the loss in a broad perfective. Why do lift-offs? Here are my top reasons.

Prepare for the Full Lifts — It’s not rocket science, but sometimes the obvious is lost when we overthink things. Various forms of education can work with athletes, but treating Olympic style lift-offs and focusing on the first pull is valuable intrinsically for many reasons, and skipping the first step is foolish. Many athletes are taught the exercise backwards or in pieces, but the reality is that one has to learn to move the bar off the ground outside of just picking it up. I can smell a hang clean only athlete a mile away when I see the bar picked up haphazardly as a means to an end. Teaching both styles of deadlifts and training the Olympic style is valuable for later advanced athletes who can perform the entire lifts.

Body Alignment Still Matters — Posture is a hot topic and I will leave the pain science to the therapist, but joints and muscles do respond to specific angles and positions. Athletes must learn the mechanical reference points to get specific muscle groups recruited and to protect against strain. Countless labs have shown that posture matters for loading in training, and heavy lifting accelerates the appreciation for improving alignments that favor performance. Proper bracing on heavy lifting requires positional awareness and range of motion, and lift-offs do it effectively.

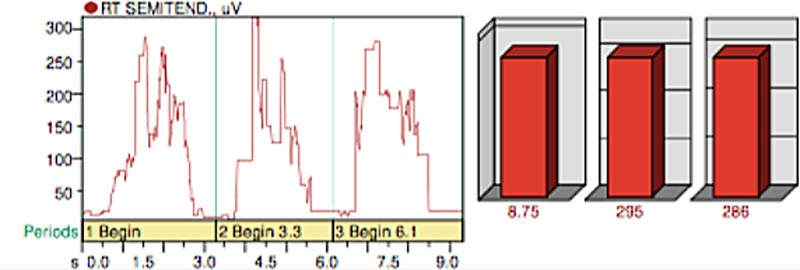

Engage the Posterior Chain — Early in a season coaches put a priority in the hips and posterior thighs to safeguard against injury and to improve performance. Seeing the data first hand I find that doing lift-offs are great in kick starting the hamstrings and gluteals. I love the fact that the legs are extending and the upper body is staying in the same position. Teaching the back to be a stabilizer rather than the propulsive agent is imperative with athletes who compensate.

Simply teaching the athlete to lift the bar up with the hips and shoulders rising simultaneously instead of pulling from the back is a great exercise in itself.

Figure 2: Surface EMG using the Noraxon system illustrates how the hamstrings are engaged during the first pull of the clean or snatch. I have changed my use of pulling style by seeing clear and measurable benefits of lift-offs.

Snatch from Blocks Regularly

I learned high-frequency block work from Zygmunt Smarlcerz by proxy from Matt Delaney years ago, but now I am seeing more and more benefits. Everyone is worried about back injuries with training, and some coaches have gone haywire with avoiding injury versus managing workloads. Snatching is lighter and has a less demanding catch, which is great for new and advanced lifters. Neophytes can do more reps to learn, and advanced athletes can tolerate more work for training needs and capacity requirements. Zygmunt is currently the head coach of USA Weightlifting and was a former Olympic champion in 1972. What I have observed first hand with several of his lifters is that injury rates are down, numbers are up, and technique has improved. Using a very short set of blocks, coaches in other sports remove the early flexibility barrier, keeping the back fresh for other training needs, such as squatting. Doing more snatching without risking injury is a great way to build a specific capacity to handle the demands of repeat power sports without the wear and tear to the foot and ankle. Snatching from blocks is also a great workaround to lower extremity injuries that are not allowing for jumping and sprinting, such as Achilles tendon problems.

Coaches can choose from three primary heights, two of them widely popular. The lowest height allows for a double knee bend and removes enough of a burden to the spinal muscles to make a noticeable difference. The second option is just above the kneecap; while it’s not engaging the same stretch reflex as the shortest option, it’s an excellent choice for teaching or for those who need a simple lift to get bang-for-your-buck power. Finally, the high box is a good option when athletes seem to be lagging in rate force development and need a little push towards a quick pop and not be too patient.

Finally, the great thing about blocks is they are useful investments to bounding exercises and can be used for jumpers and other athletes wanting to challenge jumping routines. Box jumps are commonly used with Jerk Boxes, but shallow ones are great for advanced elastic response plyometrics and stiffness routines like hops up and down.

Figure 3: Durable boxes are great for more than just Olympic lifts. If I were to put up a facility, I would focus on building equipment that can be flexible to be used for both plyometrics and Olympic lifts so that athletes have access to both tools readily.

Newbies should Press with Dumbbells

Is the jerk dead? Many programs in colleges have eliminated the jerk, and some have good reasons for it. The jerk is usually the first pattern to go from a training program because it’s often seen as part of the sport of Olympic-style weightlifting rather than a training stimulus. The jerk is less used, so teaching it becomes a problem as exercises lose favor. While not a jerk teaching tool, Push Presses and similar movements are excellent tools for all Olympic style weight lifts. I learned from Brendon Ziegler that to help with pushing through the ground, Presses with Dumbbells are great options for early learning. Dumbbells remove the bar-hitting-head problem that many newbies worry about, and the transfer for forces through the ground really help athletes learn to apply forces properly. While the jerk usually involves a split and pushing one’s body down versus pressing the weight up, the press teaches the cornerstone of lifting from a standing position, something many athletes cut out from failing to finish lifts properly.

When athletes learn how to finish, a reference point is established so that they know where they are trying to navigate towards. It’s not that the presses are trying to replicate the jerk with an overhead movement; it’s about teaching how to apply forces down to get the bar up and not cut off the power. Too many athletes mule kick or curl their feet in a stomping pattern with the Olympic lifts, and learning from Jim Snider from Wisconsin or Brendon Ziegler from Bakersfield has helped me get more out of the lifts.

Pressing with dumbbells is great only when compensations are not used, and cheating with lumbar arching is prohibited. Due to the high range of motion of dumbbells, some athletes will press too far away from their midlines, and this could be from flexibility limits as well. If an athlete is tight and unable to do the lifts safely, doing the movement anyway may solve the problem by the body learning to relax muscle groups at the right time, also known as reciprocal inhibition. While the nervous system is very powerful, it can’t solve every problem, and forcing a movement is a bad idea.

Use Conceptual Cue Words

Cue words are very popular, and they should be for good reason—many of them work like magic to help teach athletes. Unfortunately, sometimes they don’t work, and many times they make the problem worse. Various pundits have promoted the use of external cues versus internal cues, expecting that a higher form of word choice will be better than suggesting how one should grip the bar or bend their knees. The truth is, what works is highly individual, specific to the moment, and unique to the coach saying the cue word. So, the question is not just what to say or when to say it; the question is, are cue words necessary?

The reason I recommend video is that athletes are not bodies but thinking bodies that are able to see and problem solve. Athletes are amazing imitators of movement and will usually do an excellent job adopting motions after seeing them done correctly. To bridge the gap, athletes seeing themselves may allow them to self-service their own corrections, and to many coaches, this bruises the ego. Coaches like feeling important but realize that expertise is needed for athletes to achieve their best, and early improvement may justify exposure and guidance. At that moment, a little nudge with a few comments may help, but any advice, be it on cues or general suggestions, must be used sparingly to prevent what every coach knows as “paralysis by analysis.” Too much thinking slows down ballistic movements and adds to the problem. Countering paralysis by too much talking requires the coach to, in fact, talk more.

Coaches talk too much at the wrong time, and not enough at the right time. Coaches need to talk when athletes are not training, and back away when they are by being minimalists. A short explanation of the purpose and concept of exercises in advance is far better than propping up a directionless athlete later. For years, I have made the same mistake other coaches have in teaching the Olympic lifts, by mimicking or replicating the way I learned to use it as a pupil. When I was lifting at a facility for my personal interest, I was politely interrupted by Dennis Reno, a man with over fifty years of experience, who suggested a few pointers. He not only gave me some great cue words, but also explained how the body works with the bar to achieve its goal. In the past, people explained things with biomechanics and physics, and all of that helped, but it was more a logical discussion rather than excessive talk about mechanics. For example, a simple cue of having the “arms hang like ropes” illustrated that I was to not only relax my arms and keep them straight during the early part of the lift; it was about using my legs better by trusting that my lower body could provide enough power. Other ideas like getting tall, quick versus jumping or exploding were far more helpful, because while those other cues simply were not giving me the full story and tried to fix a part of the problem rather than the full need. Cues are not for the coaches to fix a movement, but provide a road map for the athlete to understand the big picture while getting them envision the correct execution.

A good take away with cues is that don’t feel obligated to follow any strict policy with internal, external, or even conceptual cues. The goal of cueing is short and effective communication, but at times, a good explanation instead of searching for the next abracadabra is a wiser choice.

Final thoughts on Olympic Lifts

Coaching the Olympic lifts is clearly more than the five tips shared in the article, but each tip shared was a milestone that I felt made an impact in my own training programs. Every year, I try to start with an empty cup and learn from anyone who has proven to develop great lifters over and over. Good advice seems to do two things with my own coaching, and most of it not only lasts a lifetime or career but just clicks and can be felt immediately. Sometimes things take a while, but many of the master coaches have the right adjustment that simply allows things to fall into place and work perfectly.

Please share this article so others may benefit.

[mashshare]Olympic Lifts – 5 Tips for Instant Improvement. Loved them all!!! http://t.co/GjgNUJCAwY via @FreelapUSA

— Jorge Carvajal (@carvperformance) August 2, 2014

Great information crucial to all coaching http://t.co/uLklBncQUO

— To be deleted (@Oldpleasedelete) August 2, 2014

Excellent work, thank you! Kinovea is proving a really useful, and free, tool for video analysis, increasing the availability of this tool. However, as you point out, it’ll only ever be as good as the video footage one records.