By Carl Valle

For decades, the use of complex and contrasting sports training methods has confused and captivated coaches. Research both supports and refutes the effectiveness of potentiation exercises. Last year, complex and contrasting methods increased in popularity again. Several articles currently in print and online review the use of potentiation techniques. However, the reality is that most fail to ask the most obvious questions that most coaches have. This article provides a full review of what coaches need to consider about potentiation methods, along with some practical thoughts on applying less-understood techniques from the scientific literature. The goals are to understand how the nervous system responds to potentiation options and to see what the long-term training strategy is in general.

Defining Potentiation

Sports scientists often label post-activation potentiation (PAP) as a phenomenon because it’s a little bit of a mystery. After a few years—10, to be exact—the author came up with a working definition that is appropriate for the general PAP response. The author thinks that a definition is important is because having nomenclature is vital to making sure everyone is on the same page. Here is my definition:

Potentiation: The temporarily enhanced neuromuscular overflow of explosive ability after a loaded resistance exercise.

After sitting down for an entire weekend reading the research again and again, I felt that the definition pointed to key factors on potentiation methods, specifically the word “temporary.” No matter what the research says with conflicting results, the common thread in all the studies is that athletes immediately perform an exercise back to back to take advantage of the neuromuscular system’s response to the previous exercise. The heart of the article and point of potentiation exercises is that they not only work intrinsically but also leave a sort of neuromuscular residue that helps the next exercise perform better than without it. There are limits, though, since fatigue is a factor and must be put into the training set-up equation. With new and controversial studies on the brain and placebo effects, the questions are as follows: What is the mechanism making the changes, and what can we do to exploit this phenomenon with athletes?

Potentiation Workout Guidelines

The long-term goal of training is to improve a specific quality, and many coaches lose sight of the long-term goal of getting better and get lost in fancy and exotic training programs. Training should have a direct and clear effect on the body, and getting too smart with workouts is common when young coaches get excited from new research or training information. When creating a potentiation workout, the first need is to make sure that both exercises are mastered. Putting the cart before the horse happens all the time, as the need to do basics correctly before more advanced options is paramount. Without being restrictive, here are four rules with potentiation training:

Advanced Athletes Only – For several reasons, I suggest that only elite athletes should do potentiation training. The first and obvious reason was stated earlier: one must master all of the exercises before combining them. Trying to learn and do them back-to-back is very difficult and even dangerous. Also, the option of doing potentiation training is a tool left deep in the toolbox, saved for when the athlete starts to plateau and actually needs something variety-wise to break through barriers without resorting to unnecessary risk-taking. Like a speed barrier, one should exhaust all the other elements and variables first before resorting to very specific methods. Like any exercise, athletes will adapt and even become flat to using potentiation-training options. I don’t like doing any potentiation until athletes reach satisfactory benchmarks with the core exercises in isolation.

Use with Small Groups – I am amazed that so many performance coaches focus so much on potentiation training when they work with large groups. Potentiation training is highly individualized and doesn’t make group training easy with facility space and workflow. With athletes moving from station to station, it’s hard to watch everyone because rest periods are now replaced with training, creating a big challenge with working with more than 4 or 5 athletes. Every exercise has a technique and risk of fatigue and athlete error, so potentiation training should be observed completely with a coach due to the fact that the loads and velocities of the exercises are demanding to the body. The difference between a circuit and paired or grouped exercises is that circuits are more for work capacity and potentiation is about pushing the envelope with power. A group of athletes doing general movements such as core training or push-ups back to back is not the same as an athlete squatting heavily and then doing a series of plyometric exercises.

Speed and Power Sports Only – Potentiation training is an advanced form of power development and should be left to sports that involve high levels of speed. Even at the elite level, endurance athletes will not reap the benefits as much as speed and power athletes will. Some research points to the fact that sufficient strength levels are necessary for exploiting potentiation training, so a 5K athlete should make sure that he or she is actually getting any fundamental and root strength development at all. A 1,500-meter swimmer needs to address strength needs, not maximize them as much as endurance and technique. On the other hand, elite soccer players may need to use potentiation training because of limited time for training; this suggests that potentiation training is more than a neurological response—it’s a practical element when time is at a premium.

Measure the Effects – If trainers didn’t manage athletes with timing and power measurements, the process would be like guesswork. For example, jumping over hurdles is difficult to measure because the height of the barriers might not indicate the true output of the athlete; it’s technical, but it’s one of the most-paired exercises after heavy squatting. Why would someone load and unload sprints when he or she is not timing to see whether the contrast is creating a faster, weight-free sprint? How does someone know whether just separating the exercises is the same or better when juggling fatigue? If you are not measuring and comparing, it’s likely that the process is dishonest. True, times are needed to get the athletes to believe into the training by buying in from expertise, but eventually, the time will come that the athletes will want to know if all of this stuff is working. Without measurements, the training is just guesswork, and no research study can replace training data.

Photo 1 – The foolish assumption that monitoring replaces testing is a current fad now, and if you don’t do real testing of speed and power, you are simply hiding. I believe in physiological monitoring, but it never replaces speed and power testing. Above is the Swedish National team in Florida doing bound testing to see the effectiveness of training blocks compared to earlier seasons.

Creating a Potentiation Workout

Designing potentiation training programs follows the same guidelines as conventional training, but several variables must be finely tuned, or one will not reap all the benefits. A good example of this is the sequence and exercise selection based on the rules above. Most coaches, when thinking of potentiation options, look at the meat of the weight room exercises and exploit those, but a better approach is to try to improve the entire workout and then look for opportunities later. A performance enhancement program will usually sprint and then lift. Very few will mix both and for good reasons; most facilities don’t have a full-size weight room at the track or have adequate speed training options next to their performance center. Another major juggle is managing fatigue, something that isn’t thought of in studies as much because they are looking at a part of a workout and not a training block. Eventually, in every sporting activity, fatigue plays a role, and with potentiation, even fatigue is a reality, and it’s likely competing against it.

Variables for potentiation are rather straightforward; the only real difference is that the first exercise in not absolute fatigue to the point of failure and the second exercise is usually faster or more power focused. Here are the three main variables and prescriptive elements with potentiation training.

Speed and Force of Contraction – Some of the research has shown that the motor unit recruitment of maximal force options creates an overflow to more ballistic or power exercises later. Very few coaches tend to go from a high velocity to a slower velocity when doing potentiation work, but it’s extremely common to design training that progresses from fast to slow. Several arguments can be made for either option, but for potentiation, it seems that heavy to fast is the most common.

Rest Period – Rest periods between exercises can range from nearly nothing to minutes, and it’s hard to prescribe a specific rest period because each exercise, each athlete, and the time of the year will correspond with the response to potentiation. The most important consideration is that a rest period and exercise pairing allows for maximal output, and measuring wattage or speed is essential to knowing if the combination is working.

Lower-Body Directed – Most of the attention of potentiation training is with lower body exercises, and for good reason. While upper body power is important, most sports are locomotive and care about lower body development for speed. Most upper body potentiation training is for throwers, NFL or rugby athletes. Sprint swimmers are also included here, but they make up a small percentage of advanced weightlifters, and most upper body sessions are only for elite world class or top NCAA levels.

Contrast, Complex, and Cluster Styles

Confusion exists about what coaches are trying to do with potentiation workouts when the terms or classifications are unknown. The most common approaches to potentiation training are the contrast options, complex pairings or groupings, and cluster style training. Cluster training is more about keeping output high by slicing the workload via rest periods, but complex and contrast styles make use of the potentiation effect instead of managing fatigue. Although cluster training does not use a rebound effect from the activation of the nervous system and is not potentiation, any manipulation of variables that increase output should be included as the similarities are enough to warrant its mention. Here are the three definitions, and just glancing, you can see similarities and differences.

Contrast Methods – A method of using two similar movements with load to create a stark and purposeful divergence in velocity.

Complex Methods – A method of sequencing exercises back-to-back with very little time between them to create a positive neurological benefit.

Cluster Methods – A method of inserting short rest periods to increase output over a given exercise bout.

How all three specifically impact training is a bit of a mystery. The first question is, what are we comparing to regarding a control option in the research? Anyone who elects to apply research must simply include what one would normally do with training, and it’s never going to be nothing; it’s usually a conventional option. So, for contrast, it would be using the same velocity for each set and seeing whether improvements happen acutely from direct acquisition. For complex methods, the combined output for both exercises must be higher than each exercise’s individual output or at least be the same with an increase in training density. Finally, the cluster proves its value over weeks to see whether maximum strength or power improves more quickly than normal compared to athletes of similar abilities.

The take away is that someone must see a direct or long-term improvement in performance speed or power that is measurable against potentiation exercises, cluster training, and other ways to manipulate the neurological output.

Photo 2: Observing the Swedish national team in person was very helpful for seeing how its exercises and training design differ from exercises and training in the United States. One example is the popularity of jump squats in Europe and Australia rather than in North America; another example is the use of bilateral exercises.

Five Popular Workouts

The author has included five good examples of popular and less-used options that many can apply or tweak for their own athletes. Each workout has a specific purpose beyond just attempting to get a neurological benefit, so the author has provided reasons for why he made certain choices for the list. Taking a theoretical idea and applying it requires some experimentation because many plans that look good on paper can’t get done because of logistics.

Contrasted Sled Sprints – The first sled article mentioned how contrast methods are popular, but the key is to see how contrast work improves acceleration better than simply doing loaded and unloaded sprinting at different times. A solution to unlocking the mystery to contrast sprinting is the internal longitudinal data collection of sprint times and estimation of the friction coefficient of sleds. It sounds complicated, but when a coach wants to know if something is working, measurement is an eventual piper one must pay. A simple solution is to see the precise speed one is doing on the back half of unloaded sprints and see if doing a weighted option increases the speed or output of the back half. Even if the output is constant, it’s in improvement if an athlete decays in speed usually.

From a logistical standpoint, contrasting every other rep is a burden, and an alternative is contrasting the first half of the acceleration work or breaking it down to reasonable chunks so that the contrast is repeated. I like the chunking method because it allows athletes to share equipment, as I prefer quality sleds over cheaper options like tires. So far, I mainly see a temporary retention of motor skills after the contrast with intermediate athletes, meaning more positive shin angles and deeper and patient body postures. This may be a reason why times appear better, but with so many variables, it’s hard to say if it is coming from potentiation of the nervous system over coordination change.

Simple Squat Complex – A timeless and popular workout is heavy squats followed by jump squats. I like using three squat modules, and the first is 4 x 5 with a very light weight (bar only). The first set is more of a warm-up squat done quickly, but not a speed squat to see how the athlete feels. The next 2 to 3 sets are jump squats to observe power without fatiguing. From there, based on the information, an athlete can do a workout that is light (overreached), normal (not overreached), or challenging (recovered). It may be the same lifts, but the second part of the complex is usually removed for those who do not feel ready, and light and normal responders should just watch and help those feeling fresh and maybe second-guess their lifestyle if they are consistently not staying with their peers.

The complex is usually done with dumbbells or barbells, but I prefer conforming sandbags and Velcro vests for speed and safety of transition. Also, I prefer higher-velocity work with elastic responses, since the eccentric demands are high and see more quality technique with the lighter load. For the heavy squatting, I prefer rep schemes 1-5, and I like 3-4 cycles only.

Double Clusters – Doubles with squatting and benching are popular because you can get a lot of work done in one set, and doing singles tend to be just that, one set, and the next athlete takes his or her turn. With double clusters, the racking allows an intermediate rest but allows three micro sets of 2 per traditional set. I rarely do cluster sets for the lower body since I prefer traditional rest, and logistically, it does take longer per athlete, so I mainly restrict clusters to benching.

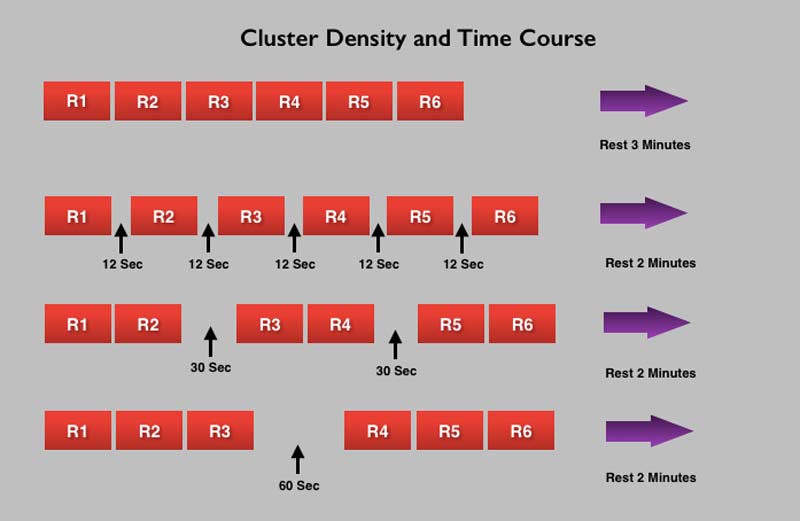

One misconception is that clusters are only for weight training, and many sprint programs and jump programs break down very intense exercises or repetitions with small rest periods to help keep the quality up without reducing volume or density. Many users of cluster reps for lower-body weight lifting must consider the fatiguing aspects of squatting when artificially increasing the output, and many athletes report a lot of soreness and fatigue, but more research needs to be done. A recent study of clustering workouts showed breaking down by singles and triples, but doubles seem to have the benefits of rest without the extensive rest required or lower outputs later. Clusters are great for improving maximal force production or keeping the quality high with jumping options or sprinting speed. Cronin and friends did a great job of looking at dividing rest into 12 seconds, 30 seconds, and one minute between singles, doubles, and triples for a 6-rep effort compared to straight sets. The results were clear; cluster options increased more output for peak power, but keep in mind that sometimes, creating fatigue creates adaptation. Again, the need to look at long-term development is essential here.

Chart 1: Cluster arrangement manipulates the density of work at the very small scale with intra rep rest periods and output with jump squats by Cronin and colleagues shows that any clustering is better than traditional sets for acute performance. How this works in the long run is a mystery.

Medicine Ball Contrast – Pairing or combining exercises or grouping based on contraction types is popular in preparing for starting speed because many sports initiation is from a stationary position. Using medicine ball throws behind the back or above the head from a squat position is a great teaching tool but requires the general power qualities to express the action. Using a 3-5 kilogram medicine ball is great motor skill reinforcement, but it’s not going to create the power to get out of the blocks more than doing extra starts and participating in a conventional lifting program. Coaches perhaps find that pairing simply removes the cheating of an elastic bounce and instills discipline not to move down or back to move forward. While some stretch reflex responses may enhance the static starting quality, they only contribute after propulsion is initiated.

Gary Winckler and Boo Schexnayder have wonderfully explained the need to not only pay attention to groupings by theme and commonalities but also send a clear message to the body to what you want it to do later. With medicine ball throws the simple motion and use of a ball distracts from the complication or paralysis of analysis many athletes have with block work. By regressing slightly, the athlete cements in a strong foundation of success, allowing for more technical details to be added later. I like three throws per block start and to explode out of the position on a designated internal clock count. The general-to-specific progression and emphasis on total body unfolding and extension tends to remove too much cueing and unnecessary coaching.

Advanced Plyometric Medley – Coaches can get into trouble when things get too complicated and a little exotic, but advanced athletes need variability and challenge to keep them progressing. Staleness, or training monotony, must be safeguarded by adding a few wrinkles without resorting to entertainment workouts that look cool on YouTube but don’t make the podium on the weekends. After years of doing the basics and polishing fundamentals, progressive overload hits a genetic ceiling, and risk tolerance must be reevaluated. A smarter way is to be smarter with construction versus adding more load or strain, but don’t get cute.

Very little research or information is available on multiple combinations, but Gilles Cometti’s work is something I think many NFL strength coaches need to see more. In 1997, I was at the Building and Rebuilding the Complete Athlete seminar, and Werner Gunthor’s video was an eye-opener. A “Mullet Monster” of 285 pounds looked more like a gymnast than a thrower, but it showed me that long-term adaptations can make a difference if done correctly. Some contraindicated movements didn’t excite me, but the ideas were thought-provoking and proven to work, unlike some recent nonsense shared at conferences.

Like any advanced option, slow progression is required, and stay away from shock methods that are just too harsh and drastic. It may be as slow as adding one extra exercise to a two-movement pattern when progressing athletes in jump sequences. The nervous system is sometimes fooled, but every coach realizes that joints and tissues are never tricked in the long run, and wear and tear must be factored in. I like limiting to four exercises tops and having a goal of synergy. Synergy means the combination is greater than the sum of its parts, so athletes need to show something later in raw testing to demonstrate its effectiveness.

Potentiation Methods Wrap Up

The window of nervous system supercompensation is similar to the post workout drink window of the past, we don’t know how much it can truly help but we do know that we need to take care of the “macros” before we worry about the “micros.” Even if the window is not as important as we thought it was, application may stay the same because it has other indirect practical values, as seen with the example exercises above. Still, we see in the research that it’s not usually reducing performance and is worth it when athletes need some sort of stimulation to keep them challenged and use the time effectively. Be warned, though, that getting hurt or failing to improve because one is seeking something interesting to the coach but not productive for the athlete is very selfish, as the basics are sometimes boring. Instead of pouring too many spices into a workout, sometimes a dash at the right time is better in the end.

[mashshare]References

Hansen, K.T., Cronin, J. B., & Newton, M. J. (2011). The effect of cluster loading on force, velocity, and power during ballistic jump squat training. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 6(4), 455-468.

Jensen, R.L., and W.P. Ebben. Kinetic analysis of complex training rest interval effect on ver- tical jump performance. Journal Strength Conditioning Res. 17(2):345– 349. 2003.

Ebben, W. P., R. L. Jensen, and D. O. Blackard. Electromyographic and kinetic analysis of complex training variables. Journal Strength Conditioning Res. 14(4): 451–456. 2000.

Please share this article so others may benefit.

Great column. Well written and informative.

Wow, you really spend some time to explain your point of view. Thank you for that! I, for myself, use the thunder and lightning method for about 1 year with great results.